EACH MONTH at the well-attended Franklin Park Reading Series in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, the writer Sasha Fletcher, author of the recently published novel Be Here to Love Me at the End of the World, assumes the ceremonial duty of reading off raffle winners to mark the end of the intermission between the show’s first and second halves. “Reading off” doesn’t quite describe it, though: what Fletcher does is scream the winning numbers in the most five-alarm voice possible, like Willy Wonka by way of Judge Doom. People laugh nervously — or genuinely, depending. Fletcher definitely has some level of awareness about all this, yet when his voice first tears through the fabric of amiable chatter, a question always flashes through the crowd: is this a disturbed person … or is it entertainment? While I personally can’t stand it, using the predictability of these eruptions to beat a retreat outdoors, I have to respect Fletcher’s commitment to craft — his performance of a guy so full of feeling, of portent, that it’s an absolute certainty some kind of crisis is in the offing and everybody had better know. Prizes, after all, hang in the balance.

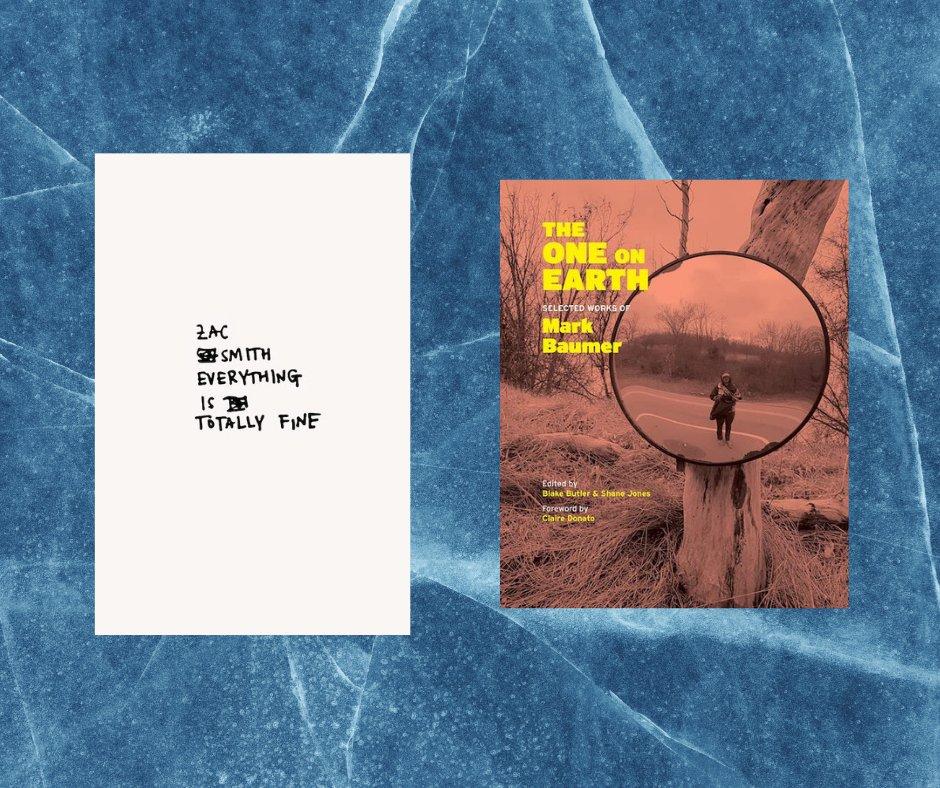

I mention this because for the first several pieces in Zac Smith’s new collection, Everything Is Totally Fine, it was hard for me not to read them in Fletcher’s raffle-scream voice. Take, for example, the story on page five, which is entitled, “When You Die, Someone Will Rip Off Your Head and Place It Apathetically Onto an Altar Dedicated to Your Ripped-off Head.” In fact, I don’t think I need to quote any more than that — the title alone will do the trick. Elsewhere in the early going is a story dubbed “Today Is Totally Fucked 2”; in a bold strike against the gods of continuity, it’s the first entry in the series to appear, meaning that you will have to make it to page 45 to find “Today Is Totally Fucked 1”: “The house started to crumble and turned into garbage. It rained. The bed turned into wet garbage. The house turned into wet garbage. I stayed in the ground.”

Another early series goes by the title “Everything Is Totally Fucked.” Then, not much later, there’s “What a Disaster!”: “My son punched me in the face again and I said, ‘What a disaster!’” Another, called “Tomatoes,” recounts a series of auto-related mishaps kicked off by our narrator throwing a tomato at the windshield of a passing car:

He started yelling at me about whether I was crazy or whatever. A cop ran his cruiser onto the curb in front of the guy’s car and tried to get out of the cruiser but the cruiser was still in drive, so he stopped mid-exit to crouch down and go back into the cruiser to shift it into park, then fully exited the cruiser.

This gag, wherein someone lets a car roll forward while trying to exit, is then repeated, verbatim, maybe four more times before the story ends less than a page later.

Here, though, are several main elements of a Zac Smith joint: 1) first-person narrator, usually a guy in the 18–30 demographic; 2) compact in duration, yet intentionally repetitive; 3) a sense of having been dashed off, in a free-writing mode, without any concern for stylistic frippery, and in fact defiantly opposed to any putting on of airs; 4) farcical pileups of cause and effect; 5) a pervasive vibe best evoked by the image of an old-fashioned strongman with an elaborately curled moustache and striped leotard running his unprotected head over and over again into a concrete wall, maybe putting a small crack or two in it, before stepping back, a little wobbly, a little worse for wear, to smile at you, the observer, instead of collapsing. Although quite possibly he will do that, too, the minute you turn away.

Who are these stories for? Most seem to have been written for the internet, where work is more likely to be encountered without context, in a slashing, here-then-gone fashion. To review this collection may be doing it a disservice; it’s the kind best plunged into without foreknowledge. What feels novel here is most effective in small doses: the majority of the stories are, no hyperbole, so stunningly bad (“This is an insanely bad story,” says Smith’s unnamed narrator on the collection’s final page) that the badness is undoubtedly part of the intent.

If you are a writer, particularly a depressed one who tends to take yourself too seriously (like, if you have seen your own face in the mirror maybe one too many times of late and are starting to question what it all amounts to, this writing game), then the work of Zac Smith may well be for you. You might find it stupid-funny, or even enlightening. You might find it infuriating. Either way, here is the spark of agency to bring you back from the brink. There is still work to do, dammit, and if Smith is out there doing what he does, there must be space for you to do what you do, too. In this sense, Smith may well be our catcher in the rye, or Miss Lonelyhearts, that body out there to prevent the wayward from falling off the ledge of the figurative cornfield and/or personals page. I thought of the fiction of Jason Porter, who tends to write vignettes of melancholic characters at the margins (though Porter’s style, by comparison with Smith’s, is high art). I thought of the ingenuousness, the boyish-rush-on-the-page voice, of Bud Smith (unrelated). There, too, you will find a trace of the sentence-to-sentence aesthetic of Tao Lin (whose Muumuu House happens to be this collection’s publisher), a certain Warholian antidramatic compression, a.k.a. “cool.” That’s true of many of the stories, if not all; a later number entitled “Coach” reads as decidedly un-Lin. I drew asterisks by the titles of two of the pieces in Everything Is Totally Fine: “Bright Future” and “The Literary Agent.” These were stories that I liked and wanted to read again.

It starts to dawn on the reader that dedicating oneself full-heartedly to the writing life, and thereby swimming hard against the capitalist imperative to find a well-remunerated purchase in this world, may not be exactly sane. Then again, going full steam ahead as a materialist, carbon-burning clone, as traditional notions of American plenty would encourage, is most definitely killing the viability of future life on the planet, while endangering the livelihoods of the youngest generation whom the parental-minded among us profess to love. And so we have to ask, who would not become paralyzed with self-doubt on stopping to think for a minute? Especially if, as a writer, the stopper-and-thinker in question means to say something meaningful about this condition?

As with the fictions of Zac Smith, the work of the late Mark Baumer follows an ethos of getting the words on the page no matter what. Carving a path through The One on Earth: Selected Works of Mark Baumer, published last June by Fence Books, you will encounter plenty of surrealist flourishes, slashing internet-friendly shorts, and an aesthetic that communicates more than anything that life is in the living, not the plotting. “This is a little sad,” writes Baumer, “but brains were never constructed to outlive earth.” A simple truth, beautifully put.

The One on Earth, as edited by Blake Butler and Shane Jones, is all about making the journey in the face of overwhelming scale. We witness Baumer’s growth, from the prank job-application letters he sent out post-college (“Before my last interview, some children threw apples at me and I had to hide behind the woodpile until dark.”); to his also prank-like, yet extremely clever and apparently convincing application essay to gain admission to the MFA program at Brown University (“I bet my mother would say, ‘Why do you keep talking about cocaine? You’re wrecking your chances.’”); to his eclectic shorter fictions (“A lot of people yelled at their televisions and told us not to crawl deeper into the wound, but we could not hear them and we continued to crawl deeper and deeper, the whole time thinking we were getting closer to our goal of reaching the inside of the ballpark where the home team was attempting to make a historic comeback which would ultimately fall a half a run short.”); to excerpts from his journals while traversing the continent on foot, including, with the deepest pathos possible, the one he wrote the morning before he died — struck in suspect fashion by an SUV as he walked along the shoulder of a Florida highway the afternoon following the 2017 presidential inauguration (“The moon was still visible but it could not save us.”); to a full-length, deeply immersive novella manuscript about two TV-enamored friends of relative privilege who seek out the kind of marginal experience and radical reimagining of the possible that comes from hitchhiking across the United States (“Leon said, ‘I am the interstate. I am a long ribbon of hot pavement. I am almost unwound.’”).

“At Some Point in the Last Nine Billion Years,” as the novella is called, shares an aesthetic with the recent Oscar winner Nomadland (2020), a here-then-gone sensory apprehension. The story, such as it is, arrives in a steadily accumulating series of discrete experiential bursts. Semi-saintly privation, estrangement, and exhaustion, coupled with the thrill of motion, an obsession with the cast-off and infinitesimal, and an abiding love of ice cream suffuse these pages. Baumer’s unnamed protagonist is forever finding the forgotten Cheeto on the floor of the car he has caught a ride in or noticing the stain of time and age spreading across the ceilings and faces he encounters, even as ruddy bodily health and a will to persevere propel him further down the line. Americans intoxicate themselves with the illusion of permanence and plenty, a well-stocked suburban home, while the pulsing crux of living gets shunted aside, rendered safely manageable, replicable, folded like pages into a novel:

An empty house that was for sale smiled at me. It said, “American comfort offers no further wisdom into the strange, unknown object that is life. Human minds tend to grow dull when lost in years of calm routine. The brain will never be satisfied with being a concept of the American suburban lifestyle because the mind always needs some new, odd experience to push against and there is nothing strange or odd left in the majority of the lives we lead.”

The above passage, a linchpin to Baumer’s work, offers just such a “strange or odd” vantage to the reader, wherever that reader may be, however the calm and quiet for reading is carved out.

The One on Earth is a gift in the truest sense, belonging to the tradition of Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley (1962), Kerouac’s many-spangled beatific catalogs, the work of Matthew Power (see “Mississippi Drift”), and of course myriad other tales of the road. But Baumer is ultimately much weirder than Steinbeck; straight-edge and environmentally conscious rather than an intoxicated rhapsode motoring for motoring’s sake; and, perhaps, prone to delving deeper into alternative modes of living than Power, who also died young, on a journey he intended to write up. Butler and Jones have curated a deeply resonant experience of Baumer’s work: the peppering of shorter pieces and excerpts primes the reader for the more meaningful immersion of the novella, while providing a surrounding context and import for its plot (two friends go on the road) that it might otherwise appear to lack. The author’s passion for activism notwithstanding, “At Some Point in the Last Nine Billion Years” never loses track of the human; Baumer doesn’t level holier-than-thou judgments — his characters are nearly always willing to acknowledge their own complicity in the American bread and circus, even while longing for transformation.

Is this a disturbed person — or is it entertainment? Faced with literary obscurity, a position at the far periphery of attention, Baumer does not make it all about himself but asks instead, “Hey, what about all this?” — a country, fellow seekers, the road. Despite his early death, Baumer has become, through the conduit of his writing and social media presence, what he set out to be: a wild and unfenced spirit in search of a new tomorrow. He’s right there on the page. Speaking as a city-dweller who has made forays into rural living, I did not know Mark Baumer, but feel like I might have. I did not know him, but would like to live more like he lived.

¤

J. T. Price’s fiction has appeared in The New England Review, Post Road, Guernica, Fence, Joyland, The Brooklyn Rail, Juked, Electric Literature, and elsewhere; nonfiction, interviews, and reviews with the Los Angeles Review of Books, BOMB Magazine, The Scofield, and The Millions. He is repped by Jonathan Agin at the O’Connor Literary Agency. Visit him at www.jt-price.com.