If you’re a literalist, One Vanderbilt is a very tall midtown office building with a new observation deck on the 91st through 93rd floors, high enough to look down on the Empire State Building. If, on the other hand, you understand that real estate isn’t real at all, that altitude is a state of mind, that a lofty view is in the eye of the beholder, and that the world is full of beholders desperate to be distracted from the panorama they’ve paid to see, One Vanderbilt becomes something else entirely. Then, the tower is merely a base for the Summit, which in turn contains Air, a full-immersion experience created by Kenzo Digital.

Air starts at ground level — or below, since you begin the journey to the skyline by descending from the street to the main concourse level at Grand Central Terminal. Any ordinary elevator in a modern office building can speed you up a quarter mile in a few dozen seconds, smoothly and silently enough that it seems like you’re going nowhere. This one, though, is special: It rattles and thumps (electronically, I trust). Lights flicker, and as a chunka-chunka rhythm picks up speed, you suspect you’re on a runaway vertical train about to get shot into the clouds. The trip reminds me of a recurring nightmare I have from time to time. Caveat epileptics.

The Summit’s website promises that the elevator will get you higher than high. “You emerge,” the promotional copy assures us, “into a boundless, structureless world, one with its own relationship to physics and time.” That sounds alarming, but relax: Your head doesn’t in fact go spinning off into the atmosphere by itself, and you don’t find yourself suddenly back in fourth grade. Instead, you file down a hallway that’s been bathed in uniform orange light, like a down-market James Turrell. Then you enter a large room and stand on a mirrored floor (visitors are advised not to wear skirts) beneath a mirrored ceiling, catching repetitive glimpses of yourself in mirrored walls. It could almost be one of Yayoi Kusama’s popular Infinity Mirror Rooms, only less mind-expanding. Some visitors stretch out on the floor, which may be a good idea if you’ve timed your day correctly and the edibles are starting to kick in. In a separate space, an array of shiny metal blobs scattered across the floor turns out to be a real Kusama (“Clouds”), though inthis corporate context it looks more like shavings from one of Anish Kapoor’s chrome kidneys. Silver balloons fill yet another room, wafting on updrafts, crowding your field of vision and recalling Andy Warhol’s Silver Clouds.

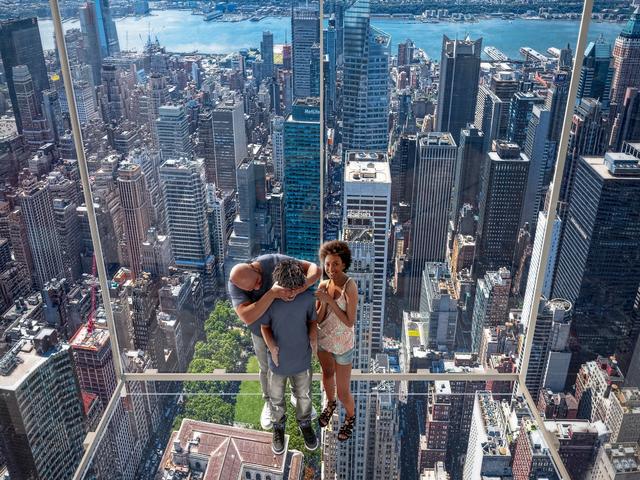

Photo: Sukjong HongThis entire Museum of Knockoffs is enriched by a soundscape of rumbles and electronic whooshes of the kind we’ve been trained to associate with mechanical failures in outer space. When it really gets going, it’s manic and loud enough to block out thought, not to mention the panicked howls of children. The woo-woo walk-through continues upstairs, where an icily cozy café with a gas fireplace in the corner (designed, like the rest of theinterior spaces, by Snøhetta) provides a refuge from the wind-battered outdoor deck. An extra 20 bucks buys you a few seconds in a glass elevator that glides up the side of the building from deck to tip so that the view becomes that much more astronomical. So do ticket prices: The whole shebang, one cocktail included, comes to $83 per person.

I went at sunset, when the gods obliged by striating the sky in gold, cyan, and mauve and Times Square echoed from down below with its own polychrome aurora. A battered, partly dormant midtown put on its old glitter, and the Chrysler Building seemed coyly aware that, although One Vanderbilt has made it harder to see it from below, the new neighbor has also supplied it with a fresh crop of admirers above. Midtown’s stalkiest newcomers — 432 Park Avenue, 111 West 57th Street, Central Park Tower — pose to the north like movie stars on a red carpet. They, too, were built as lookouts, and they are a reminder that in New York even the loftiest view is temporary. When the 1,646-foot 175 Park Avenue goes up barely a block away, Summit’s visitors will practically be able to read computer screens in the topmost offices.

Kenzo Digital’s installation seems calculated to compete with the show. Mutating LED displays reflect on the glass walls, as if trying to out-glitz Manhattan. The slick, disappearing floor tempts you to look at your feet (clad in disposable booties so as not to scuff the mirrors) rather than out. In one ultra-bar-mitzvah-worthy gimmick, you can have your face scanned then deconstructed as a moving cloud and projected on a wall-size bank of video screens. Air treats the city as a stage set, a backdrop for the razzle-dazzle on offer indoors. There were times when I suspected that the warp-speed elevator had wafted me not to the 91st floor but to the 3rd, and that, as I gazed out over Manhattan, I was surreptitiously being wrapped in a high-res projection. Reality looked like a simulacrum.

Summit is not the only high-altitude, high-priced observation deck to pad the experience with glitzy extras. One World Observatory, which opened atop One World Trade Center in 2015, makes the elevator ride part of the show, hurtling visitors upward through New York’s evolution from wooden farmhouses to glass needles. The Empire State Building recently reconceived its observatory, regaling visitors with videos while they’re standing in line and leading them through a sequence of historical exhibits. In one corner, King Kong’s paws have punched through masonry walls and now seem stuck, as if the tower were a giant cookie jar. The Edge, at Hudson Yards, turns the observation deck into an architectural feature, jutting out from the building’s head like a duck’s bill.

Why does a developer take three of the most desirable floors of an office building off the market and open them to the public? Because an observation deck is a cash cow. There’s a reason that the Edge just sold to the KKR private-equity firm for $500 million: Until tourist attractions shut down in March 2020, the Empire State, One World, and Top of the Rock were each roping in 2 million or 3 million visitors a year, and each operator felt the need to offer something more than the same old pièce de resistance the other guys had. If you’re going to get customers to pay $30 to $40 a pop for a view or even more, you’d better give them something better than just … a view. The people want packaging.

New York is the ultimate immersive artwork. You can only really experience it from inside and at sidewalk level, where you pick your own way through a fragmented, constantly shifting field of vision populated by extras and enriched by a randomized soundscape. And yet, as that collective masterpiece evolved, it sprouted a whole architectural form devoted to seeing it from a distance. The only reason supertall buildings keep getting erected is that they offer aerial perspectives on their own habitats. At this height, the real thing looks fake, a composite of toy skyscrapers, tinfoil rivers, pinprick traffic lights, Central Park the size of a welcome mat, and some sort of nature in the hazy distance. From 1,000 feet up, the city feels like an object on a table — a big object, containing an infinitude of gearworks and dollhouse dramas, but even so, a bounded thing.

F. Scott Fitzgerald felt the disappointment of the all-encompassing vista when he went to the new Empire State Building’s observation deck in 1932: “Full of vaunting pride the New Yorker had climbed here and seen with dismay what he had never suspected, that the city was not the endless succession of canyons that he had supposed but that it had limits … And with the awful realization that New York was a city after all and not a universe, the whole shining edifice that he had reared in his imagination came crashing to the ground.”

That “awful realization” has been endlessly seductive, though. It causes developers to put up penthouses on a stick and plutocrats to buy them, perhaps because when your connection to the city is tenuous, you prefer to see it at a safe distance and keep it behind glass. The real-estate business — one tiny golden sliver of it, anyway — keeps finding fresh ways to commodify chunks of the city. New York from above is a brief and noiseless spectacle, one that Kenzo Digital treats as an amenity in need of a boost. In an interview with the Times, the artist allowed that Air “can’t solve all the problems.” But, he continued, “I hope it can inspire an entirely new generation about this city and this neighborhood.” I can understand the need to ward off Fitzgeraldian letdown, but surely there’s a better way than assaulting them with lights and mirrors. If, in order to thrive in the coming decades, midtown really did need this overpriced, overproduced festival of tackiness, then New York would be in serious trouble.

Photo: Courtesy of SUMMIT/One Vanderbilt