Last October, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors paused the LA County Sheriff’s Department’s ability to hire certain non-sworn personnel, while also freezing $143.7 million in sheriff’s department funding.

The move was meant to pressure Sheriff Alex Villanueva into addressing the department’s major budget deficit, caused mostly by significant spending on overtime and “under-realized revenue” — contracts and grants the department was expected to win, but either lost, or failed to apply for in the first place.

On Tuesday, the supervisors voted unanimously to unfreeze $82.7 million, a portion of which is allocated for coronavirus-response efforts.

There are a couple of notable caveats, however, due to the sheriff’s ongoing budget issues.

Deeper in the Hole

Last year’s motion tied the return of the $143.7 million to whether the sheriff would work with the CEO’s Office to develop “budget mitigation” strategies.

The problem is that the sheriff is expected to be even deeper in the hole by the end of this fiscal year (-$89 million) than last year (-$63 million), an outcome made even more serious by the fact that the coronavirus crisis will require significant budget cuts across the board.

“Last year, the county had sufficient fund balances to cover the sheriff’s department deficit because of the county practices of good budget policy,” said Supervisor Hilda Solis. “We also warned that the county may not have the financial means to address” a future shortfall. “And, of course, look where we are now.”

Now, pandemic-related budget cuts are expected to hit up to a billion dollars in lost revenue for the county during the current fiscal year, with another one billion or more lost during fFY 2020-2021.

With this in mind, motion authors Supervisors Sheila Kuehl and Hilda Solis, proposed the board release to the sheriff $75,100,000 for regular operations and $7,600,000 for expenses related to COVID-19, while also reducing the department’s academy classes from 12 back down to 4 classes per year, “previously approved” in the department’s budget. According to the supes, this would effectively erase $49 million of the budget gap. The sheriff tripled the classes to address understaffing issues, but the increase has forced the department to use sworn staff working overtime to assist the training classes.

That spending now would have eventually paid for itself many times over, however, according to the sheriff.

The academy’s boosted flow of new deputies into the LASD’s ranks, he said, would have resulted in $400.2 million in overtime savings over a period of five years, after an initial investment of $49 million in recruit training. More deputies on the roster would mean less overtime spending.

“Each academy class we run,” the sheriff said, saves “$10 million in annual vacancy overtime,” while also reducing officer fatigue and liability.”

“All the local academies run by community colleges are currently inoperable,” said Villanueva, “which means that our local police departments are using the sheriff’s academy to sustain their staffing as well.” And cities that contract with the sheriff’s department already suffer from having fewer deputies than they ask for, he said.

Sheriff Says Supes Are Purposefully Underfunding the LASD

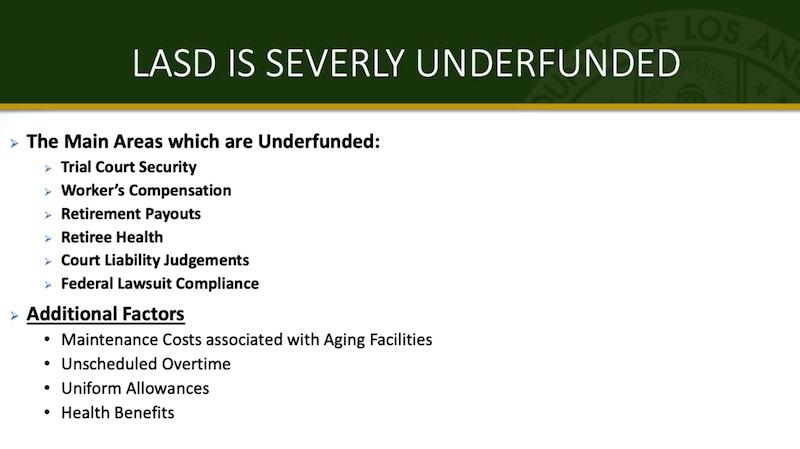

As Villanueva sees it, the Board of Supervisors has “deliberately” kept necessary funding from the sheriff’s department over the last five years. Thus, the LASD’s budget was not able to grow at the same pace as the overall county budget.

Additionally, the sheriff said his administration had to pay for big-ticket items, like keeping up maintenance on aging jails, and health benefits for members of the “baby boomer generation” who Villanueva says are retiring “en masse.” Meanwhile, he said, the department has reduced worker’s compensation claims this year, and overtime (when compared to last year), while reducing violence in the jails and the “quality of care” within the jail system.

County CEO Sachi Hamai refuted the worker’s comp claims, saying that fewer actual claims has not meant reduced spending in this department. IN 2017-18, claims cost $172 million. This year, it’s $213 million. “I think that’s probably a more important indicator,” Hamai said.

“By defunding the sheriff’s department, you’ve exacerbated the issue of us being underfunded in all of these major categories,” Villanueva said, referring to a list of systems and services his department must provide.

The sheriff further accused the supes of “playing politics with public safety and falsely portraying the financial status of the LASD for political gain.”

Not handing over control of “the remaining $61 million of the sheriff’s department funds included in this motion,” Villanueva said, will negatively affect the LASD’s ability to provide public safety services.

“We’re doing our job in very trying times, and we need you to work with me,” the sheriff said.

But all other county departments have successfully balanced their budgets, and the sheriff has had plenty of time to work with the CEO’s Office on ways to recoup the deficit, according to Supes Kuehl and Solis.

The Sheriff’s “Sense of Exceptionalism”

“The sheriff has such a sense of exceptionalism about his department,” Kuehl said, “that it’s honestly an insult to the fire department, the probation department, the children’s services department, all the health departments, because they all need more money.”

Yet, “they have all stepped up,” and “presented a balanced budget,” she said. “They are all working with us, except for this one department. More than a quarter of all the county funding … goes to the sheriff’s department.”

During Tuesday’s meeting, Supervisor Solis asked CEO Hamai explain how the LASD arrived at a second deficit year — even worse than the first — despite the board’s insistence that the sheriff partner with the CEO’s Office to remedy the situation.

During weekly budget deficit mitigation meetings, Hamai and her staff have “consistently asked, even up until now” for documents from the sheriff’s department “and have not received any of the information” they requested. In January, during a semiannual budget status update, Hamai said, is when the CEO’s Office and the sheriff’s department successfully identified “about $70 million in solutions.”

“However, to date, we’re only able to confirm that they were actually able to achieve $19 million of the $70 million,” Hamai told the board.

The CEO requested information on the “sheriff’s mitigation plans, particularly in the area of overtime, since many of his positions were being filled,” the CEO said. “To date, we have not seen any of that documentation.” Which, “brings us up to the forecast for closing this year’s current budget at approximately $88 million” over, she added.

“You have made every attempt and effort to try to meet with the sheriff’s staff since January, I’m assuming?” Solis asked. “And we have yet to receive outstanding mitigation plans for the remaining $51 million in solutions?”

“Since the fall, we have been meeting and requesting this information,” Hamai said. “And again … we have not received it.”

Misdemeanors and Felonies

When asked what legal consequences a department head, elected or otherwise, might face by closing the year with a deficit, LA County Counsel Mary Wickham described “significant” consequences that “could include even criminal action, as viewed under the law — up to a misdemeanor.”

In response, the sheriff told the board that he “could go on for a long, long time” about “felony crimes and the consequences” — crimes that are “done by public officials.” But, the sheriff said, it would “be inappropriate to make that inference in any form, much less in a budgetary debate.”

“So good luck with that, if you’re going to scare me with the claim about a misdemeanor crime.”

Supervisor Kathryn Barger did not let the comment slide.

“I don’t know if that was a veiled threat or what you were referring to,” said Barger. “I just wanted to say for the record, that I didn’t appreciate that comment.”

What did appear to scare the sheriff, however, was an amendment to the motion that will temporarily block all promotions within the department.

Sheriff Must Abide by Promotional Freeze Along With Rest of County Departments

Villanueva called the move “bombshell” of a “surprise announcement,” in an email statement after the meeting.

“I want you to rethink what you just added on today to this motion,” the sheriff said during the meeting. “These are your field supervisors out there in patrol. These are your floor sergeants in custody. These are your watch commanders.”

But all departments have been directed to put promotions on hold in light of the pandemic situation.

“I was alarmed to hear,” Kuehl said, that in spite of the hiring freeze on the sheriff’s department, and “a promotion freeze in every department,” in just one week period between April 16 and April 23, the sheriff put through 44 promotions. I’m talking this April. Just last week.” These new promotions will dig the sheriff’s department deeper into the budgetary hole, the supervisor said.

With that, Kuehl introduced an amendment to the motion to establish a promotional freeze for all positions. If the sheriff wants to fill a particular position, he should “work with the CEO to justify the need. Kuehl stressed that all county departments are currently subject to this freeze, but that she wanted to “make it very clear that that also applies to the sheriff’s department.”

“We certainly cannot allow the department to continue growing their deficit, especially in the current economic climate,” Kuehl said.

Not a Decision Made Lightly

Supervisor Janice Hahn, when it was her turn to comment, said that she felt “conflicted” about the situation, and was concerned by aspects of the proposed actions.

“I’m frustrated, Sheriff, that you haven’t been able to figure this out … that your budget deficit is just not going to be sustainable,” Hahn said. “Having said that, I want to say how important the sheriff’s department is to us.” The contract cities in Hahn’s district “love their sheriff’s deputies,” the supervisor said.

While Hahn said she supported the decision to release funding to the department, she said she was “less excited about limiting the classes” and thus, affecting hiring. “I do know there’s a correlation between overtime and not having enough hires, so I’m conflicted with that.”

Hahn ultimately requested that the promotions-related amendment be pulled out as a separate motion, abstained from voting on that motion, and voted, along with the rest of the board, in favor of the larger motion to return control over $82.7 million to the sheriff, while reducing academy classes.

“All we are doing in releasing this $83 million,” Kuehl said in closing, “is saying: this is a lot of money, Sheriff. We agree that you need more money. Here it is. Spend it as a sheriff should.”

Photo: Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva virtually attends the April 28 Board of Supervisors meeting.