Located about 42 km away from the city of Tiruchirappalli in Tamil Nadu lies the Musiri Panchayat town. Being situated on the banks of the Kaveri river, the abundance of water makes the land fertile and well suited for agriculture.

Due to high groundwater levels in the region, regular toilets do more harm than good. If the sewage is not disposed of properly, this can severely contaminate the water. This observation is what made the Society for Community Organisation and People’s Education (SCOPE) introduce Musiri to Ecosan toilets.

In this system, there is no flush or a piped connection to a sewage system, meaning that there is no way for any water body or groundwater to get polluted.

AdvertisementThe first ever Ecosan toilet in Kalipalayam village was built in 2000. By 2005, they had perfected their techniques, building the first community toilet system which had seven toilets each for men and women, and another for the old and infirm.

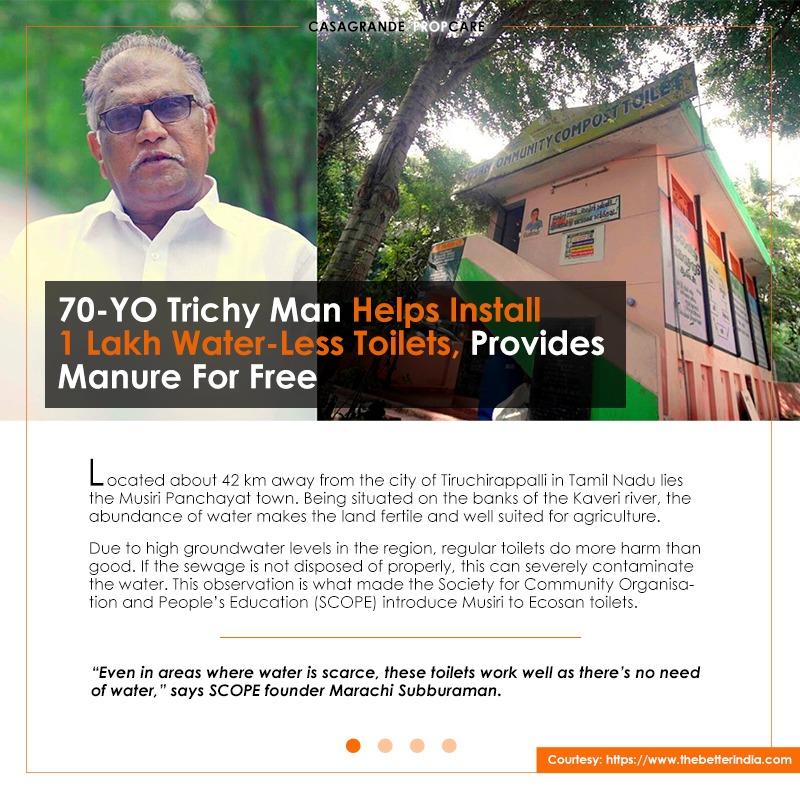

In Tamil Nadu alone, SCOPE has installed about 20,000+ toilets in Tiruchirapalli. The organisation was founded in 1986 by Marachi Subburaman with a focus on rural development.

Once SCOPE came into existence and started engaging with villagers at a grassroots level, they found that open defecation was a huge issue in the region. This was when they started constructing toilets.

AdvertisementSo far, SCOPE has constructed over one lakh toilets across 26 states in the country and carried out bigger projects in Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Assam.

What’s special about SCOPE’s toilets

Subburaman explains that Ecosan toilet systems are suitable for areas with rocky terrain where the construction of septic tanks has challenges. “Even in areas where water is scarce, these toilets work well as there’s no involvement of water,” explains the 70-year-old.

The entire toilet unit has two pans with one cavity each–one to defecate, another to urinate. The pans also have a space for washing. Each of these cavities connects to different pits at the bottom of the structure. The toilet is built above the ground, and the units are connected to a pit which collects the waste.

AdvertisementThe base is made up of concrete to prevent any contact with groundwater. Moreover, urine and excreta are collected in separate chambers in the pit through pipes connected from the toilet unit, and are treated to be used as urea and manure for agriculture.

Once the cavity for excreta is used, ash is sprinkled.

“In Musiri, you find these grasses which are used for sowing mats. These are sometimes burnt and sprinkled across the cavity which connects to the faecal chamber. This ash not only has antibacterial properties, but also speeds up the preparation of manure as it absorbs all the moisture,” explains Subburaman.

Advertisement“Since the moisture content in the region is very high, we wait for 6-12 months before opening it, so that the compost is ready,” explains Subburaman.

Per year, each toilet unit produces about 400 kg of manure, while the community toilets produce 1,177 kg of manure, which is given to farmers for free.

Several farmers from Musiri say that they previously spent about Rs 20,000 a year on manure and urea, but the free agricultural inputs have helped them cut costs.

AdvertisementEach of these cost about Rs 30,000. In case of the community toilets, the cost is higher. “When we first started, we were charging about Rs 8 lakh for the community toilets. Currently, we charge Rs 15 lakh due to an increase in the cost of construction materials. This amount can go up, depending on the number of toilet units and the size of the structure,” says Subburaman.

All of these toilets are installed through different rural development projects in collaboration with other NGOs, organisations and CSR projects.

About the founder

Subburaman pursued a BSc degree in Chemistry from Periyar E.V.R College in Tiruchirappalli in 1975. The following year, he enrolled for a B.Ed from Siddhartha College of Education in Tumkur. In 1976, he joined Village Reconstruction Organisation (VRO), an NGO in Guntur, which works towards the construction of cost-effective homes in rural areas.

Advertisement“I worked with VRO for ten years until 1986. Father Michael Windey, the founder, inspired me to work in rural areas. That is how I went on to found SCOPE in 1986,” says Subburaman.

When SCOPE first began, it carried out all kinds of activities. They helped different village communities earn an income through modes other than farming, like promoting weaving, tailoring, and animal husbandry. They also closely worked with foreign-based NGOs like Action For Food Production (Afpro) to improve agricultural productivity.

Related Stories Couple Quits City-Life, Helps 10000 Rural Women Understand Sexual & Reproductive Rights20 Inspiring Villages Giving Life to India’s Vision for a Self-Reliant FutureAdvertisementTheir foray in sanitation began with the construction of leach pit toilets across different villages in Tiruchirappalli. These toilets are water-less, with circular pits being dug on the ground. These were first introduced to reduce the negative impacts of open-defecation.

AdvertisementHowever, Subburaman heard of Ecosan toilets when he attended a sanitation workshop in Chennai and met Paul Calvert, an engineer from Belgium.

“Paul was living in Thiruvananthapuram at the time and studying the fishing community in the area. At the workshop, he spoke about the benefits of Ecosan toilets. This is how I came across them in 2000,” says Subburaman.

He started developing these toilets, and finally, the first Ecosan toilet in the Kalipalayam village was installed.

Challenges and plans

Although SCOPE’s work across the country is commendable, they faced a lot of challenges in their journey.

“People were reluctant to use the toilets, regardless of the fact that they were free. Most said they were more comfortable defecating outside. They did not want to believe the negative impact on health and environment that open defecation entailed,” explains Subburaman.

To counter this challenge, SCOPE started paying the users. For each day that they used the toilet, they were paid Re 1.

They continued this for four years until they saw an improvement in the number of users. “Every year, we would end up spending about Rs 12,000 while paying the users. In four years, we spent about Rs 48,000 and WASTE, an NGO based in The Netherlands, helped us finance this,” says Subburaman.

They also conducted workshops and awareness camps about the hazardous impact of open defecation so that villagers would willingly use the toilets.

Despite these challenges, SCOPE has worked with organisations like UNICEF in several states.

“UNICEF was working with us to implement several rural development programmes. When they heard that we were starting work in the sanitation sector, they worked with us on projects in Assam, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu among other states,” he says.

In Kerala, they constructed about 100 Ecosan toilets in the aftermath of the 2018 floods. In total, they have built over 28,000 Ecosan toilets with UNICEF alone!

Now, what does Subburaman hope to achieve?

“In our country, the disposal of faecal sludge is abysmal. When it is time for people to clear the septic tanks, they dispose of all the waste either in the open or in water bodies, causing severe environmental damage,” he points out.

He hopes that the waste management authorities across the country set up treatment plants for faecal sludge. This would reduce environmental degradation and contamination of resources. ”

I see great merit in water-less Ecosan toilets. They achieve the twin goals of reducing open defecation and contamination of resources. In the end, I hope to contribute to making the country 100 per cent free from open defecation,” he signs off.

You May Also Like: Pune Duo Convert Old Buses Into Ladies’ Toilets That Have Been Used Over 1 Lakh Times

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)